Reading Connections: “Real” Stories & Why They Matter Now

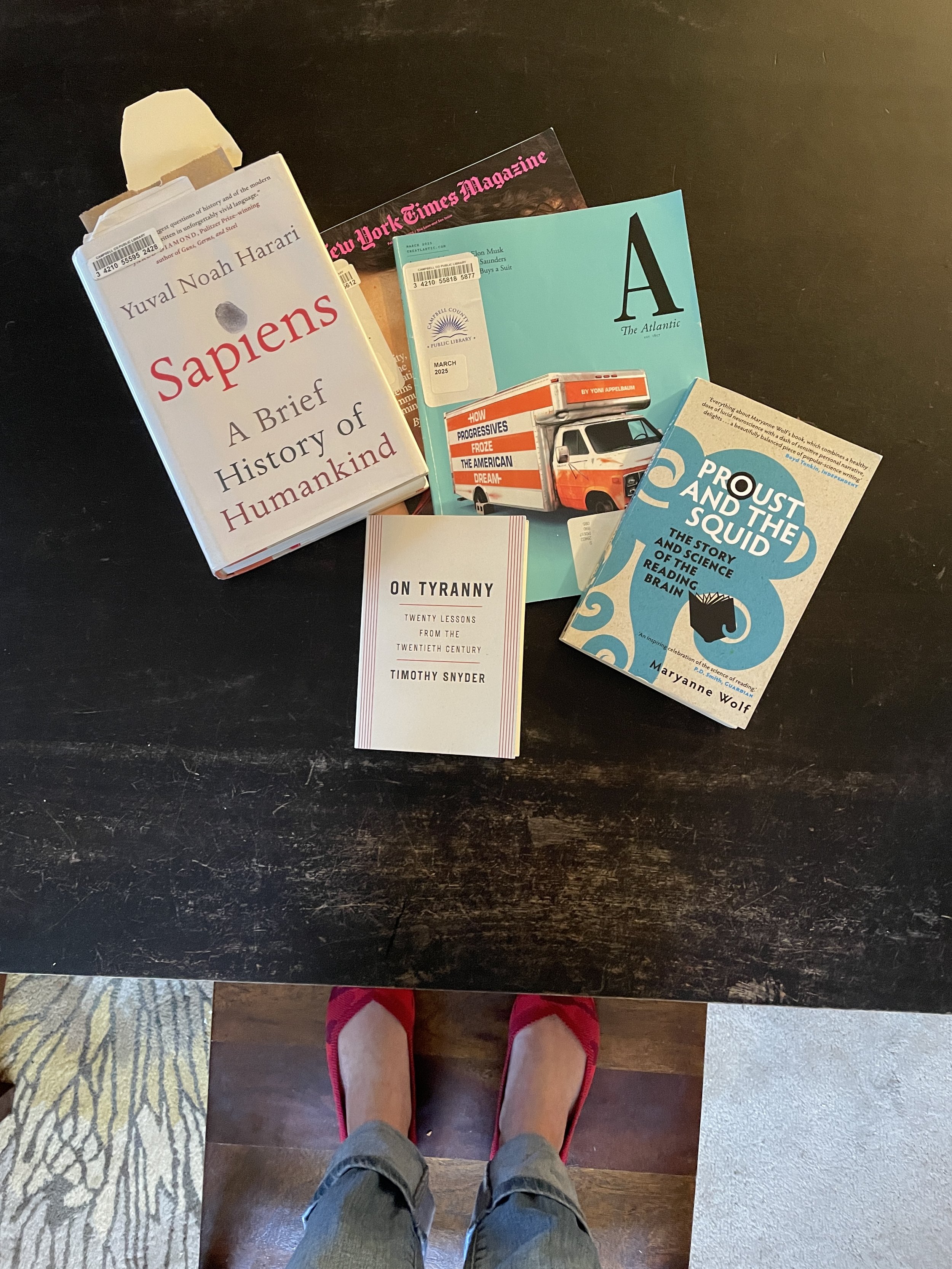

My current stack of reading material — and a peek at my first pair of Rothy’s (which I have to say are totally living up to the hype!).

There’s a quality to our current moment that draws me to the tactile sensation of reading something real — in all senses of the word. Right now, I’m reading all non-fiction, toggling between books and magazines. Two of the books I own, and my six-year-old daughter was sweetly scandalized when she saw me underlining and writing in the margins of Proust and the Squid (it’s forbidden in the kids’ books we own, and certainly not allowed in library books!). I hadn’t marked up a book in quite some time, and it was a very satisfying sensation. Even the library book is bristling with bookmarks (random papers and kid art) to help me find the passages I want to note down for later reference.

One thing I adore about reading is that it stimulates the brain’s impulse to make connections — both from text to text and from page to real life. In this post, I’ll share a shorter snippet for a quick snapshot of why each thing I’m reading MATTERS NOW, plus a deeper dive if you want to delve further into how I’m digesting the ideas I’m uncovering.

Snapshot Snippet

1. Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain

By Maryanne Wolf

Why It Matters Now

At literally the same time I’m reading this book and gaining a new, deeper appreciation for how we as humans learn to read, I’m also witnessing my middle daughter, age 6, become what Maryanne classifies as a “decoding reader.” Suffice it to say, I’m amazed.

Reading has always felt like second nature to me, but this book reveals what a true miracle it is that we humans have acquired the ability despite the brain not being built for the process at all.

Read this if… you want to find out the Herculean efforts your brain goes through to read and write, and how that particular combo is what allows us to think new thoughts.

2. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century

By Timothy Snyder

Why It Matters Now

If you’re paying attention to what’s happening in our government, you’re probably feeling frightened to some degree. This pocket-sized book validates those feelings, and offers firm footing to help us navigate this tricky time in our political history.

Read this if… you want a clear-sighted perspective on current events coupled with historical context that brings everything into clear focus. Then share it with your friends. I was gifted my copy by a friend.

3. “Stuck in Place: Why Americans stopped moving houses—and why that’s a very big problem,” from the March issue of The Atlantic

By Yoni Appelbaum

Why It Matters Now

Checking out this issue of The Atlantic from the library was inspired by one of the suggestions from On Tyranny (connections, don’t you see??). This article is so fascinating, toppling some long-held assumptions of mine that simply are untrue from a historical perspective. Namely that most families in most towns in America stay put for generations. While it is truer now than it has ever been, that is a NEW development. We used to be more mobile by literal magnitudes.

Read this if… you have wanted to maybe move across town, to a new city or different state and been stopped in your tracks by cost, job opportunities or housing availability. The answers to why this is happening and what may be done about it will surprise you.

4. Sapiens

By Yuval Noah Harari

Why It Matters Now

I think maybe the only way forward for us as humans is to gain a thoughtful understanding of how exactly we’ve gotten here in the first place. I’m within 100 pages of finishing this sweepingly ambitious read, and It’s frankly blowing up my brain. So many of the “baseline assumptions” that form the foundation for all our belief systems simply aren’t… objectively true? Infallible? Good? Yuval is an incredible writer (matter-of-fact and laugh-out-loud funny at unexpected moments) who is making me question everything.

Read this if… you want to look at humankind with fresh new eyes. Beware: Nothing is sacrosanct here, neither religion, nor marriage, nor capitalism, nor democracy.

My current short stack of non-fiction reading.

Deep Dive

Oh, you’re still here! How lovely. Welcome to a more long-winded look inside my brain…

1. Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, by Maryanne Wolf

“When you learn to read you will be born again… and you will never be quite so alone again.”

- Rumer Godden

“Reading is an act of interiority, pure and simple. Its object is not the mere consumption of information… Rather, reading is the occasion of the encounter with the self… The book is the best thing human beings have done yet.”

- James Carroll

The Miracle of Reading

Did you know that it’s basically a miracle that humans can read and write? Unlike spoken language or hearing, there’s no specific area in our brain dedicated to reading or writing. Instead, humans have created complex processes that have allowed us to essentially cobble together connections across multiple parts of the brain so we can repurpose areas originally meant for other functions to enable us to automatically register words and their meanings. There’s no gene associated with reading or writing, which means each and every human being has to acquire the ability to read and write basically from scratch.

As someone who’s always taken reading and even writing for granted, it’s been fascinating to uncover all the insanely hard work it takes to achieve the high-level fluency that allows our brains to move at hyper speed behind the scenes so that other areas of our brain can contemplate the meaning.

Also, it’s made me appreciate my mom anew. Very sadly, she’s lost the ability to read as part of the disease process of Alzheimer’s, but in the many decades before that she was a teacher with a specialization in teaching reading. Thanks to the vivid lessons she drilled into me, I’ve subconsciously given my children a great gift I didn’t fully realize I was giving. At literally the same time I’m reading this book and gaining a new, deeper appreciation for how we as humans learn to read, I’m also witnessing my middle daughter, age 6, become what Maryanne classifies as a “decoding reader.” Suffice it to say, I’m amazed.

I always knew English was particularly irregular and somewhat difficult, but this poem Maryanne includes in her book really drives the point home—with humor, to boot:

“I take it you already know

Of touch and bough and cough and dough?

Others may stumble, but not you

On hiccough, thorough, slough, and through?

Well done! And now you wish, perhaps,

To learn of less familiar traps?

Beware of heard, a dreadful word

That looks like beard and sounds like bird.

And dead; it’s said like bed, not bead;

For goodness sake, don’t call it deed!

Watch out for meat and great and threat,

(They rhyme with suite and straight and debt).

A moth is not a moth in mother.

Nor both in bother, broth in brother.

And here is not a match for there,

And dear and fear for bear and pear,

And then there’s dose and rose and lose—

Just look them up—and goose and choose,

And cork and work and card and ward,

And font and front and word and sword.

And do and go, then thwart and cart.

Come, come, I’ve hardly made a start.

A dreadful language? Why, man alive,

I’d learned to talk it when I was five.

And yet to read it, the more I tried,

I hadn’t learned it at fifty-five.

-Anonymous

English Is So Weird

In addition to observing my daughter actively acquiring the skill of reading, I’m struggling alongside my third grade son (8.5) studying for difficult spelling words, like gnarly, lodging and other prickly selections. Understanding how our language was developed gives me a new perspective on this painful process.

“The English language is a similar historical mishmash of homage and pragmatism. We include Greek, Latin, French, Old English and many other roots, at a cost known to every first- and second-grader. Linguists classify English as a morphophonemic writing system because it represents both moprhemes (units of meaning and phonemes (units of sound) in its spelling, a major source of bewilderment to many new readers if they don’t understand the historical reasons…. In essence, English represents a ‘trade-off’ between depicting the individual sounds of the oral language and showing the roots of its words.”

Take muscle for example. The c is silent, which makes no sense from a phonemic standpoint, but all the sense in the world if you know the Latin root musculus, and related words like muscular and musculature.

Reading + Writing = Thinking New Thoughts

“Every child who learns to read someone else’s thoughts and write his or her own repeats a cyclical, germinating relationship between written language and new thought, never before imagined,” writes Wolf. It’s a generative relationship! The very act of reading and writing together makes us able to come up with brand new ideas.

Wolf calls this process the gift of time. Once we achieve reading fluency, our brains can understand the words so quickly that there’s enough time leftover for us to contemplate their meaning. “… the act of reading silently invited each reader to go beyond the text; in so doing, it further propelled the intellectual development of the individual reader and the culture,” explains Wolf. “This is the biologically given, intellectually learned generativity of reading that is the immeasurable yield of the brain’s gift of time.”

Furthermore, it’s a type of virtuous circle. “In other words, the new circuits and pathways that the brain fashions in order to read become the foundation for being able to think in different, innovative ways,” as Wolf describes it. Using these pathways again and again builds the capability further, accelerating and supercharging the process. It’s what I’ve felt in periods of high productivity fueled by huge amounts of reading and writing.

Writing = Refining

“In his brief life, Vygotsky observed that the very process of writing one’s thoughts leads individuals to refine those thoughts and to discover new ways of thinking. In this sense the process of writing can actually reenact within a single person the dialectic that Socrates described to Phaedrus. In other words, the writer’s efforts to capture ideas with ever more precise written words contain within them an inner dialogue, which each of us who has struggled to articulate our thoughts knows from the experience of watching our ideas change shape through the sheer effort of writing,” writes Wolf.

Maybe this explains why my favorite journaling technique is, in fact, a dialogue where I write back and forth to a level of my consciousness I call Higher Wisdom, or HW for short. This entity entirely of my own creation is infinitely wiser than me, asking probing questions and offering sage insights that blow me away every time.

The Future of Reading + Writing

We’re in a crazy period of accelerated change right now fueled by the almost unimaginable power of AI. No matter if we like it or not, want it or want to resist it, tools like ChatGPT will fundamentally alter how we read, and even moreso how we write.

Wolf included this excerpt from the futurist and inventor Ray Kurzweil in her book:

We can have confidence that we will have the data-gathering and computational tools needed by the 2020s to model and simulate the entire brain, which will make it possible to combine the principles of operation of human intelligence with the forms of intelligent information processing. We will also benefit from the inherent strength of machines in storing, retrieving, and quickly sharing massive amounts of information. We will then be in a position to implement these powerful hybrid systems on computational platforms that greatly exceed the capabilities of the human brain’s relatively fixed architecture.

How can we, limited by our current brain’s capacity for 1016 to 1019 calculations per second, even begin to imagine what our future civilization in 2099—with brains capable of 1060 calculations per second – will be capable of thinking and doing?

Tasks like note-taking, research, brainstorming and rough drafts are already faster, more efficient and more fun in partnership with widely available and inexpensive AI tools. But it’s crucial we retain our reading and comprehension skills, resisting the urge to simply skim, copy-paste and call it done. And yes, we should absolutely outsource tedious writing tasks such as documentation or even outlines and rough drafts to AI. But we must continue to exercise our own writing and editing muscles to avoid atrophy. Add AI to your process, don’t let it replace the process.

As for me, I continue to do my writing work myself because the process allows new ideas to percolate and form, and the editing process stimulates refinement and even epiphany.

2. On Tyranny, by Timothy Snyder

One of my reading obsessions has long been fictionalized accounts of the human triumph amidst tragedy during World War II. I can’t now look at our current political circumstances without seeing terrifying parallels between Trump and Hitler. This book, published in 2017, succinctly lays out the commonalities, citing historical examples that drive home the danger. It also offers clear-eyed advice for what to watch out for and what we might be able to do if it comes to the worst (and before that day comes as well).

One section in particular speaks to me: Be kind to our language.

“Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. Make an effort to separate yourself from the internet. Read books,” advises Snyder. He goes on to write about how television news feeds can almost induce paralysis by the sheer overwhelming waves of information.

“Politicians in our times feed their cliches to television, where even those who wish to disagree repeat them. Television purports to challenge political language by conveying images, but the succession from one frame to another can hinder a sense of resolution. Everything happens fast, but nothing actually happens. Each story on televised news is ‘breaking’ until it is displaced by the next one. So we are hit by wave upon wave but never see the ocean.”

Instead of gaining space for proper perspective, we’re bombarded by overwhelming waves. “The effort to define the shape and significance of events requires words and concepts that elude us when we are entranced by visual stimuli,” writes Snyder.

The tonic, he suggests, is to take time away from the internet and from television and spend time immersed in books and print magazines and newspapers. “When we repeat the same words and phrases that appear in the daily media, we accept the absence of a larger framework,” warns Snyder. “To have such a framework requires reading. So get the screens out of your room and surround yourself with books,” he suggests.

And in case you don’t get to this pocket-sized, highly digestible quick read, here’s a lightning-fast recap.

1. Do not obey in advance. In other words, don’t anticipate what those in power want and give it to them before it’s demanded. This goes for media entities, companies, brands and individuals. When you have a seat at a pertinent table, use your voice.

2. Defend institutions. Many of our institutions are crumbling around us, but the press holds strong and our judiciary is fighting back. We simply cannot assume that “rulers who came to power through institutions cannot change or destroy those very institutions—even when that is exactly what they have announced that they will do.”

3. Beware the one-party state. For heaven’s sake, vote. Consider running for office if you can. Defend the rules of our democratic elections.

4. Take responsibility for the face of the world. “The symbols of today enable the reality of tomorrow.” Remove swastikas and other signs of hate – do not grow desensitized.

5. Remember professional ethics. Do not work for the enemy. “It is hard to subvert a rule-of-law state without lawyers, or to hold show trials without judges. Authoritarians need obedient civil servants, and concentration camp directors seek businessmen interested in cheap labor.”

6. Be wary of paramilitaries. “When the pro-leader paramilitary and the official police and military intermingle, the end has come.”

7. Be reflective if you must be armed. This is for those whose job requires carrying a weapon: Be ready to say no to orders. “Without the assistance of regular police forces, and sometimes regular soldiers, the Nazis could not have killed on such a large scale.”

8. Stand out. “It is easy to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. Remember Rosa Parks. The moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken, and others will follow.

9. Be kind to our language. Use your library – I just checked out real print magazines, and have been reveling in them.

10. Believe in truth. “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.”

11. Investigate. This is one of my favorite points. Have you ever written a news story? You might want to try to see what kinds of effort and thinking goes into such an endeavor. “While anyone can repost an article, researching and writing is hard work that requires time and money. Before you deride the ‘mainstream media,’ note that it is no longer the mainstream. It is derision that is mainstream and easy, and actual journalism that is edgy and difficult. So try for yourself to write a proper article, involving work in the real world: traveling, interviewing, maintaining relationships with sources, researching in written records, verifying everything, writing and revising drafts, all on a tight and unforgiving schedule. If you find you like doing this, keep a blog. In the meantime, give credit to those who do all of that for a living. Journalists are not perfect, any more than people in other vocations are perfect. But the work of people who adhere to journalistic ethics is of a different quality than the work of those who do not.”

12. Make eye contact and small talk. Interacting in real life can quickly reveal people’s real nature—which is part of knowing whom you can and cannot trust.

13. Practice corporeal politics. Literally, don’t let yourself become bodily soft and isolated. Get outside, move your body and connect with others in real life.

14. Establish a private life. Don’t hang your dirty laundry in public. “Remember that email is skywriting. Have personal exchanges in person. For the same reason, resolve any legal trouble. Tyrants seek the hook on which to hang you. Try not to have hooks.”

15. Contribute to good causes. Donate to non-profits that do good in our society.

16. Learn from peers in other countries. They have a perspective that could be hidden from you, and also it may be that the savviest solutions require alliances. Are your passports up to date? Make sure they are.

17. Listen for dangerous words. “Be alert to the use of the words extremism and terrorism. Be alive to the fatal notions of emergency and exception. Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary.” This is straight from the Nazi playbook, as explained by the legal theorist Carl Schmitt. Snyder paraphrases: “The way to destroy all rules… was to focus on the idea of the exception. A Nazi leader out-maneuvers his opponents by manufacturing a general conviction that the present moment is exceptional, and then transforming that state of exception into a permanent emergency. Citizens then trade real freedom for fake safety... People who assure you that you can only gain security at the price of liberty usually want to deny you both.”

18. Be calm when the unthinkable arrives. “Modern tyranny is terror management. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power. The sudden disaster that requires the end of checks and balances, the dissolution of opposition parties, the suspension of freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial, and so on, is the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book. Do not fall for it.”

19. Be a patriot. A nationalist is not a patriot. “A nationalist encourages us to be our worst, and then tells us that we are the best. Nationalism is relativist, since the only truth is the resentment we feel when we contemplate others… A patriot must be concerned with the real world, which is the only place where his country can be loved and sustained. A patriot has universal values, standards by which he judges his nation, always wishing it well—and wishing it would do better.”

20. Be as courageous as you can. “If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny.” That’s literally the sum total of chapter 20, by the way.

3. “Stuck in Place: Why Americans topped moving houses—and why that’s a very big problem,” from the March issue of The Atlantic, by Yoni Appelbaum

Moving Day

Have you ever heard of Moving Day? It was news to me that many American cities throughout the 19th and into the 20th centuries used to have a dedicated Moving Day, “‘quite as recognized a day as Christmas or the Fourth of July,’ as a Chicago newspaper put it in 1882.” While the dates varied from city to city, with many celebrating in the spring and others in the fall, the overall vibe was the same. “For months before Moving Day, Americans prepared for the occasion. Tenants gave notice to their landlords or received word of the new rent. Then followed a frenzied period of house hunting as people, generally women, scouted for a new place to live that would, in some respect, improve upon the old. […] These were months of general anticipation; cities and towns were alive with excitement.”

If this seems a strange idea now, it’s because time and culture have shifted dramatically, especially in the last 50 years.

- In the 19th century, 1 in 3 Americans moved in any given year.

- In the 1960s, 1 out of 5 Americans moved in a given year.

- In 2023 – that number was only 1 in ever 13 Americans.

Could you afford to move houses now? In the same city? To another one? Switch states?

So what the heck happened exactly? Yes, there’s a housing shortage. But that’s only part of the picture. “… many Americans are stranded in communities with flat or declining prospects, and lack the practical ability to move across the tracks, the state, or the country – to choose where they want to live. Those who do move are typically heading not to the places where opportunities are abundant, but to those where housing is cheap. Only the affluent and well educated are exempt from this situation; the freedom to choose one’s city or community has become a privilege of class.”

The causes of our stagnation are just as complex and tangled as the consequences, but I’ll attempt a gross oversimplification here.

Causes

In a word, zoning. Also historical preservation. Collectively, the urge to keep things how they are (and implicitly or explicitly keep others out) through rules and regulations effectively stifled the type of freeform, organic growth that allowed cities to flex and change to accommodate an influx of dream-seekers.

Here’s an example in the West Village of NYC. Zoning blocked efforts to change neighborhoods, to tear down a 3-story brownstone in favor of a 6-story apartment building, for example. Beginning in the 1960s, where the “neighborhood had always grown to accommodate demand, to make room for new arrivals – now it froze.”

Blue state bureaucracy. Despite progressive insistence on inclusion and equality, liberal states are the worst offenders when it comes to exclusive zoning. “…when the share of liberal votes in a city increased by 10 points, the housing permits it issued declined by 30 percent,” writes Applebaum

Consequences

Gentrification that effectively shrinks neighborhoods that once had the ability to grow exponentially. It also makes neighborhoods exclusively for wealthier inhabitants, with no room for the poor.

Limited options for where to move. Most people can no longer afford to move to progressive cities which offer the most employment opportunities. Instead, their choice is to move to where there’s still affordable housing, in places where there might not be as many work options.

Less money. Overall, people could be much wealthier if there were more feasible options to move to the cities with the most productive U.S. metropolitan areas: New York, San Francisco and San Jose. If these 3 cities “had constructed enough homes since 1964 to accommodate everyone who stood to gain by moving there… would have boosted GDP by about $2 trillion by 2009, or enough to put an extra $8,775 into the pocket of every American worker each year,” explains Applebaum.

Here's another example: “If a lawyer moved from the Deep South to New York City, he would see his net income go up by about 39 percent, after adjusting for housing costs—the same as it would have done back in 1960. If a janitor made the same move in 1960, he’d have done even better, gaining 70 percent more income. But by 2017, his gains in pay would have been outstripped by housing costs, leaving him 7 percent worse off. Working-class Americans once had the most to gain by moving. Today, the gains are largely available only to the affluent.”

More insular behavior. Did you know the greeting “Howdy, stranger” is tied to the mobile nature of our American ancestors? Think about how open-minded this simple phrase truly is. New faces are not met with suspicion, but welcome. But what if you’re stuck with the same neighbors, the same tribes and factions year after year, generation following generation? If you’ve ever lived in a small town, you know exactly what this can feel like. In a stagnant environment, people can double down on their existing relationships, fearful of new neighbors and different ideas. There’s a joke in my small town, that you’re considered “new” until your family’s lived here for at least two generations.

“The key to vibrant communities, it turns out, is the exercise of choice. Left to their own devices, most people will stick to ingrained habits, to familiar circles of friends, to accustomed places. When people move from one community to another, though, they leave behind their old job, connections, identity, and seek out new ones,” Applebaum writes.

“American individualism didn’t mean that people were disconnected from one another; it meant that they constructed their own individual identity by actively choosing the communities to which they would belong.”

What’s the way out?

The author offers several potential solutions that could reverse the trend of stuck-in-placeness, but it really all boils down to loosening up on zoning and permitting restrictions—and being consistent and fair about the ones that are applied.

1. Allow others to build new housing on their own property by paring back restrictive zoning regulations

2. Ensure all rules are applied uniformly and consistently across a city (not tailored toward specific neighborhoods)

3. Be tolerant of the changing aesthetic, regardless if you think a new duplex is ugly or an apartment building interrupt the flow on a residential single-family street

4. Build an abundance of new housing, in the country’s most prosperous urban areas – about 3 million units per year!

4. Sapiens, by Yuval Noah Harari

I’m within 100 pages of finishing this sweepingly ambitious read, and It’s frankly blowing up my brain. Here’s a taste of why:

1. Creating collective fictions (believing together things that don’t exist right now) is THE REASON homo sapiens are the dominant species today, and not Neanderthals for example.

2. Things that have resulted in the expansion of the human population are not necessarily good for individual humans. Case in point: transitioning from hunter-gatherers to planter-growers resulted in more hard work and less calories per person per day, on average. Who did get more for less? The wealthy.

3. Money is our biggest, scariest and most successful shared fiction. It even transcends religion.

4. The genius of religion is that it allowed MASSIVE groups of people to organize and work together due to a shared belief system.

5. Science + imperialism supercharged each other—literally one couldn’t have existed without the other. (Someone has to pay for science, after all.)

6. We are cruel to animals, almost without thought, currently utilizing them the exact same way we would harness any kind of energy source, inanimate or otherwise.

7. Capitalism is just as much a religion as Christianity, Islam or Buddhism. We just don’t like to think of it that way. And it’s flawed, deeply flawed.

8. The recognition of (or creation of, perhaps) inherent human rights is an impressive achievement—but we can do better. What’s best for one individual can be at odds with what’s best for the collective good, for example. And what about the inherent rights of animals, who share many of our psychological needs and urges?